|

by Balázs Gulyás, Rupshi Mitra, Ajai Vyas, Shaik Muhammad Amin, Valentin Gulyás and Parasuraman Padmanabhan

Summary

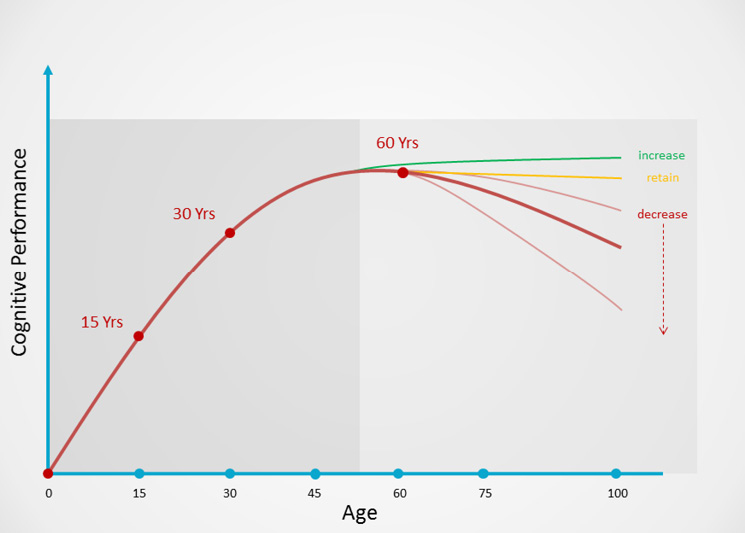

s life expectancy increases worldwide, more and more emphasis is being put on healthy aging, especially healthy cognitive aging. The main question is: how to improve our capacity to use our full cognitive abilities for as long as possible. The general concept is that as people get older they start to show a decline in their cognitive capacities, but a large number of scientific observations obtained in recent years, primarily based on large cohort longitudinal studies and observations obtained in ‘Blue Zones’, indicate that this is not necessarily the case. In aging populations, there are always a good number of people who can retain their cognitive abilities until the end of their life, and some who steadily increase their cognitive performance. This phenomenon – cognitive resilience – can serve as the basis for our deeper understanding of how to preserve our cognitive abilities in the later stages of our life. s life expectancy increases worldwide, more and more emphasis is being put on healthy aging, especially healthy cognitive aging. The main question is: how to improve our capacity to use our full cognitive abilities for as long as possible. The general concept is that as people get older they start to show a decline in their cognitive capacities, but a large number of scientific observations obtained in recent years, primarily based on large cohort longitudinal studies and observations obtained in ‘Blue Zones’, indicate that this is not necessarily the case. In aging populations, there are always a good number of people who can retain their cognitive abilities until the end of their life, and some who steadily increase their cognitive performance. This phenomenon – cognitive resilience – can serve as the basis for our deeper understanding of how to preserve our cognitive abilities in the later stages of our life.

Brain Aging and Cognitive Aging

Today it is commonly known that life expectancy is increasing worldwide, the population of the world is rapidly aging, and the percent of the population ages 60 and above is expected to double from 11% to 22% within 50 years from the onset of the 21st century.1 In Singapore, this same age group will doubled from 220,000 in 2000 to 440,000 and is expected to increase to 900,000 by 20301 and to one and a half million by 2050.2 Parallel with this, the number of physical and cognitive impairments along with diseases related to aging are increasing.

Due to this demographic shift, if the present trend in the age related cognitive inabilities and diseases is continued, they will rapidly hike in the near future. With reference to the global statistics in 2013, there were around 44.4 million people with dementia. However, this count will elevate to 135.5 million by the mid-21st century.3 In Singapore alone, the prediction is that in 2050, 187,000 cases of dementia will have been reported.4

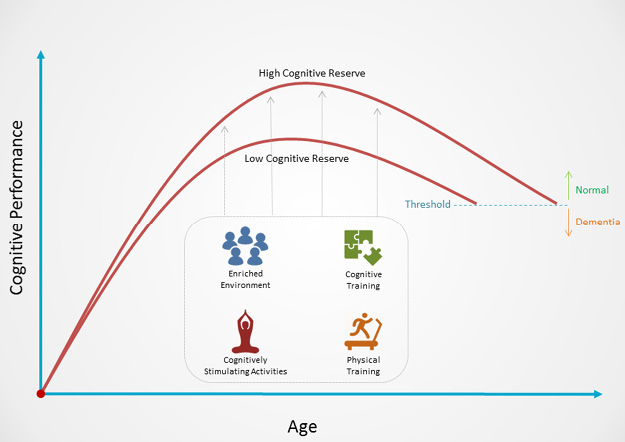

Earlier the general concept of cognitive aging was that around age 65, parallel with the decline in our physical abilities, our cognitive abilities start to decline and this decline can be more rapid or slow. A rapid or significant loss of our cognitive abilities results in dementia and the person will be in need of regular or permanent social care. But long term observations and large cohort longitudinal studies indicate that a certain proportion of the aging population can retain their cognitive abilities and there is a minor fraction of the population which can even increase it.5 This phenomenon is often referred to as cognitive resilience (Fig.1).

For everybody interested in healthy aging and optimal cognitive aging, the question arises: How do we study these people? How do we learn the lessons from those who have a long life with retained cognitive abilities? What advice can we give to others and ourselves regarding the maintenance of our cognitive abilities?

How to Study the Phenomenon?

One of the pioneering studies in this regard was initiated in North America by Dr David Snowdon in 1986. He started a longitudinal study on Catholic nuns, members of the School Sisters of Notre Dame religious congregation, living in seven convents across the United States. The sisters allow access to their personal and medical histories, undergo rigorous annual mental and physical testing, and pledge to donate their brains for research after they die. The study has provided us with one of the best insights into the neurobiology of aging. The study provided groundbreaking information on some aspects of aging as well as information on the possibilities to prevent pathological aging, in particular Alzheimer's disease.6

Maintaining an active and productive life into old age is one of the most important preventers of mental decline. This is complemented by, among other remarkable aspects of their regulated life, social activities in the community, intellectual activity (most commonly: teaching), diet and, yes, spiritual life. According to David Snowdon, the health problems of old age are not caused by aging but rather by the diseases that can accompany aging.

But the North American Nun Study is only one of the several on-going large cohort longitudinal studies worldwide, which aim to understand the mechanisms of maturation and aging in various domains, including Sweden's Betula Study,5 the Study of Adult Development at Harvard Medical School,7 the 1958 UK National Child Development Study, the British Cohort Study, the Millenium Cohort Study8 all contribute with a richness of observations to our better understanding of aging.

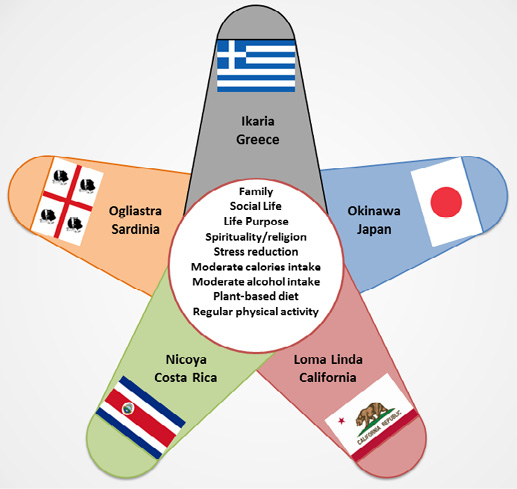

In recent years, some very remarkable observations have come from studying the so-called Blue Zones: areas where life expectancy is exceedingly long.9 These zones include Okinawa in Japan; Sardinia in Italy; Nicoya in Costa Rica, Icaria in Greece and the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, California. Some even add Georgia in the Caucasian Mountains and a few other blue zones to the list. Original studies identified at least five major contributors to the longevity of the people in these zones: Family centered life, no or minimal smoking, vegetarianism or semi-vegetarianism, regular physical activity and legumes. Additional factors, which have also been identified, include the identification of life purpose, stress reduction, moderate calories intake, regular consumption of curcumin, turmeric, polyphenols, moderate alcohol intake, engagement in spirituality or religion, and engagement in social life (Fig. 2).

What is Cognitive Resilience?

In general, resilience has been described as the capacity to bounce back from traumatic life events. Observations show that about 10-15% of war veterans survive the scars of war with a graceful and optimistic outlook, quite in contrast to most others who succumb to post-traumatic stress disease (PTSD), high anxiety and phobic memories of war. Similar observations have been made with survivors of political or natural catastrophes. Yet, the resilience of war memories is only one subset of varying resilience capacities across many different situations. In a way, the aging process is a test case for studying human resilience, including cognitive resilience. A minority of us emerge behaviorally-cognitively stronger with aging as we are sharper in our mental faculties, calmer in our disposition and more hopeful about life itself. In brief, a small percentage shows high level of resilience to stress among the aging population.

The neurobiological bases of cognitive resilience have been explained by various factors, of which the theoretical concept of Cognitive Reserve may play a key role. This concept postulates that greater lifetime engagement in cognitively stimulating activities modifies neural networks that ultimately reduce the negative effects of age-related changes or brain pathology. The factors that contribute to an increased cognitive reserve include educational attainment, occupational attainment, engagement in leisure activities, the integrity of family and social networks, lifetime experiences, IQ and EQ (emotional intelligence).

Studies on cognitive reserve in normal aging indicate a slower cognitive decline in memory, executive function and language skills in subjects with higher literacy skills as well as in those regularly using two or more languages in their communication. Similarly, a number of studies show that the risk of dementia is reduced in subjects with more than 8 years of education, with higher lifetime occupational attainment and in those who participated in a variety of leisure and social activities.

How do We Achieve Cognitive Resilience as We Age?

Although detailed further explorations are needed to understand the intricate relationship between longevity and cognitive resilience, the general concept is that they go hand in hand. Most recent studies, including those in animal models as well as those based on observations in aging human populations like the ones related to longitudinal cohort studies or studies on the Blue Zones, have converging conclusions and emphasize a number of critical factors to obtain longevity, including our relationship with our natural and built environment, with our social environment, with our internal environment called the 'human biome' as well as diet, physical activity and cognitive activity. Naturally, in this regard, no serious research denies the role and importance of our genetic endowment, and in recent times, more and more emphasis is put on the above factors. The so often quoted “nature versus nurture” or “gene versus environment” duality of all higher biological phenomena in aging related scientific discussions is usually replaced by “gene versus lifestyle” duality. And though magic recipes do not exist, increasing evidence suggests that longevity and life-long cognitive resilience is in our hand as our lifestyle is a critical factor in these We can work on our cognitive resilience and increase it by proper actions and attitudes during our lifetime (Fig. 3).

Relationship with our Natural and Built Environment

The nature of the living environment is drastically changing around us. Those who lived in sleepy kampongs a few decades ago now live in high-rises. More and more people are living in cities, crammed in concrete jungles missing the natural environment. Urbanization today will have many implications on how our mental faculties fare during aging. The mismatch between an environment full of nature where our bodies evolved to exist and the relatively non-naturalistic environment of the modern cities is not without consequences.

Several observations have led to an increasing realization that the environment of urban living may contribute to significant psychological problems and, the more, can significantly affect our aging, in general, and, by effecting the cognitive reserve, our cognitive aging, in particular. A general conclusion is that a city environment, may be an improvement regarding sanitation and public health matters and thereby may contribute to an improved living standard, can be bad news for our mental health and cognitive resilience. Given the urban environment of city states like Singapore, this conclusion poses some urgent imperatives on policymakers and healthcare providers.

So, what can we do with urbanization and what can we do as a city? The challenge, and the opportunity, both lie in the strong influence of the built urban environment. We can change how we build our cities. Humans have an innate tendency to psychologically orient themselves to nature, life and its varied forms. Observations of this tendency have led to the ‘biophilia hypothesis’. From our perspective then, the presence of nature in our immediate urban environment can contribute to alleviate the consequential effects of urbanization on psychological health and can increase our cognitive reserve. For instance, several recent research studies have been dedicated to demonstrate the ‘greening the brain’ effect of walking around in greenery in contrast to doing the same in a busy, noisy, smoky, hazy urban environment.

Packets of greenery, parks, gardens, green corridors, and all forms of natural enrichments in our city environment are important in this regard. The use of these green spaces reconnects us with nature, benefiting both our cities and our minds. And they contribute to our physical recovery as well as connective reserve and, consequently, to our healthier cognitive aging.

Relationship with our Social Environment

The social environment comprises a wide variety of interactions between the individual and her/his family members, closer and wider social circles and more beyond the interpersonal relationship. Human animal interactions, with special regard to household cats and dogs coming into the fore in this context and in our new era dominated by the internet, the social media and artificial intelligence also enter into our social sphere. A rich network of family and social relations, relatively intensive social interactions, engagement in leisure activities, and even companionship with household pets has been shown to increase the aging brain's tolerance to neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive decline.

Relationship with our Internal Environment, the Gut Biota

The human gut microbiota is a very complex ecosystem of billions of microorganisms that live in the human digestive tract. The gut microbiota is different in newborns, children, adolescents, young and old people, as it undergoes a gradual change in its composition and metabolic functions with aging. The dietary pattern influences the composition and metabolic functions of the gut-microbiota. However, short and long term dietary patterns have different effects on the composition and function of the gut-microbiota. For instance, in older people, the reduction of certain bacteria in the gut microbiota, enhances several gut-related diseases. In addition, there are more roles of gut-microbiota in the gut-brain access via various already known and not yet identified mechanisms, including the synthesis and processing of neurotransmitters. Thus, the changes occurring in gut-microbiota in elderly people are mostly due to diet, environmental factors, and inflammatory developments which might be associated with brain function.

Experimental evidence supports the active role of gut brain axis in the gut-brain signaling. Furthermore, the gut-microbiota changes in its composition and functions as people age, thereby affecting cognitive functions. However, the gut-microbiota function and composition can be normalized by adopting a suitable diet and therefore enhance the cognitive performance of the elderly population.

Diet

Closely related to our internal bodily environment is the question of what we eat – our food and diet.

Nutrition has clearly demonstrated to be one of the modifiable risk factors for pathological aging and cognitive decline. It is realized that various dietary patterns affect our cognition and its change with aging. In the focus of the researchers’ interest are two approaches in these days. One approach is a hypothesis driven approach: observations indicate clearly that certain diets, for instance the so-called Mediterranean diet contribute to longer life expectancy and higher cognitive resilience. Other approaches are more ’data driven approaches’ in the sense that they do not formulate a prior hypothesis about the efficacy of a diet, they simply analyze large databases involving a great many observations on larger populations’ eating habits.

Hypothesis driven dietary pattern studies include various well established historical and geographical developed diet patterns such as those of the Mediterranean diet pattern. It studies the dietary indexes such as Healthy Diet Indicator (HDI), Healthy Eating Index (HEI), Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and so on. The Mediterranean diet pattern is rich in plant foods such as cereal, legumes, nuts, fruits and vegetables, as well as in fish and olive oil, which act as a primary source of mono-unsaturated fatty acids. It is usually complemented with red wine rich in polyphenols. It is considered as one of the healthiest diets.

In recent years, numerous studies focused on the various physiological and cognitive consequences of Mediterranean Diet and resulted in valuable observations, including the facts that high energy intake of mono-unsaturated fatty acids functioned as a protective factor against age related cognitive decline. It was associated with less brain atrophy and better cognitive performance than diets with meat consumption, and it tends to minimize the chances of developing mild cognitive impairments and Alzheimer's Disease adherence.

Other approaches analyze large populations with special regard to their diet and aging patterns. For instance, studies conducted on the elderly male population in Finland, Italy and the Netherlands with the help of the HDI. A study, investigating the relationship between the dietary pattern (measured in terms of HDI) and cognitive function (measured in terms of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)), concluded that cognitive performance increases with elevation of HDI, as chances for the onset of cognitive impairment is low when the HDI score is high. Later, the same experiment was replicated with purposeful extensions in the food intake and cognitive performance assessment test in Italy and the results from this experiment were in close relation with the North European study, clearly indicating that a healthy diet induces better cognitive functioning in elderly people.

The DASH diet is rich in fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy products and it mainly consists of low levels of saturated fat and cholesterol. It is used as one of the dietary patterns to reduce hypertension. In recent studies it was observed that the subjects who underwent DASH and DASH with weight management exhibited greater neurocognitive improvements than those who remained on the usual diet pattern. The study of diet in aging, and in the retaining and improving of cognitive resilience is a new discipline in our times and we can expect in the near future quite elucidate observations from such studies.

Physical Activity

One of the best studied aspects of sustained cognitive fitness is related to physical activity. A large number of studies, including both cross-sectional and randomized control intervention studies, show that there is a positive association between regular physical activity and cognitive functions in general and in older age there is a clear association between physical fitness and cognitive functions and performance.10

Not only physical well-being, fitness and resilience but also cognitive fitness and resilience are improved by exercise and physical activities in aging. Though a number of both structural and functional changes in the human brain have already been described as the effects of physical activities, we still need to understand better the mechanisms whereby physical activities enhance cognitive functions.

In this context, one more important observation that is coming to the forefront is that: physical and cognitive training mutually enhance each other and result in synergistic effects regarding the enhancement of cognitive resilience and cognitive functions.

Cognitive Activity

One of the most important aspects of increasing our cognitive reserve and improve our cognitive aging is sustained cognitive activity. Intellectually stimulating activities have been reported to provide a “protective effect” by increasing our cognitive reserve and cognitive resilience and providing us with increased flexibility, and adaptability of brain networks underlying cognitive functions.

Education is definitely an early source of intellectual stimulation that could lead to better performances across the lifespan eventually leading to greater cognitive reserves. A serious challenge is that the illiteracy rate worldwide is still very high: in 2009, 800 million adults have been reported as illiterate. In today's rapidly aging population, two-thirds of people with dementia live in developing countries where the prevalence of illiteracy is the highest worldwide. Consequently, interventions to enhance cognitive reserve and thereby cognitive resilience and to promote healthy cognitive aging in older adults with elementary education clearly have strong health policy implications.

The association between years of formal education and literacy with cognitive resilience has been demonstrated widely. Subjects with higher rates of cognitive resilience demonstrated less cognitive impairment during aging, independent of cerebrovascular lesions, when compared to those with no formal education. And not only literacy acquired in childhood, but also literacy acquired in adulthood has its effect: the latter has been shown to profoundly refine cortical organization in both the visual cortices and language centers of the brain. All these learning-based processes may enhance the brain's capacity to modify itself through learning, known as neuroplasticity.

Similar effects have been observed with bilingualism, which has been reported to induce neural changes that provide powerful means to enhance cognitive resilience. For this reason, the promotion of bi- or multilingualism helps the enhancement of cognitive resilience, too.

Conclusion

The more we study cognitive aging, the more we understand about its basic neurobiological mechanisms as well as about lifestyle related activities which may contribute to healthier cognitive aging. Diet, physical and mental activities, our relationship with our environment, whether it be social, physical or biological, are critical game changers to healthy cognitive aging. All play an important and interrelated role to improve our cognitive reserve and cognitive resilience.

References

- https://www.gov.sg/news/content/singapore-feeling-impact-of-rapidly-ageing-population

- https://www.populationpyramid.net/singapore/2050/

- http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/ageing/ageing_facts/en/

- http://alz.org.sg/dementia/singapore/

- http://www.org.umu.se/betula/betula/

- David Snowdon: Aging with Grace: What the Nun Study Teaches Us About Leading Longer, Healthier, and More Meaningful Lives. Bantam, 2001. pp. 256.

- https://www.hms.harvard.edu/psych/redbook/redbook-family-adult-01.htm

- http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/page.aspx?sitesectionid=851

- https://bluezones.com/

- Gajewski, P.D. and Falkenstein, M. Physical activity and neurocognitive functioning in aging – a condensed updated review. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity 13(2016):1.

A detailed reference list is available at http://conic.ntu.edu.sg/Research/Pages/OurPublications.aspx

|

Prof Balázs Gulyás, is Professor of Translational Neuroscience at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine (LKCMedicine), Nanyang Technological University. Prior to this appointment in 2013, Prof Gulyás spent most of his scientific career at the world-renowned Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, where he is still a Professor in the Department for Psychiatry, Division of Clinical Neuroscience. Prof Gulyás has made significant contributions to the field of functional brain mapping with positron emission tomography (PET), in particular to the localization of cortical areas in the human brain related to visual perceptual functions, visual memory and imagery, olfactory and pheromone-sense functions. More recently, his research focused on molecular neuroimaging with PET, focusing on neurological and psychiatric diseases and their “humanized” animal disease models. Prof Gulyás can be contacted by email at balazs.gulyas@ntu.edu.sg

Assistant Professor Rupshi Mitra is from the Division of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, School of Biological Sciences, NTU. From 2005 to 2010, she did research on gene therapy to protect against stress related disorders, and the use of sensory enrichment to mitigate chronic stress effects. Her current research projects include Connectivity of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in simple and complex housing living environment; How does enriched environment promote resilience? In search of brain mechanisms; and Neuroscience of Psychological Resilience. Prof Mitra can be contacted by email at RMitra@ntu.edu.sg

Assistant Professor Ajai Vyas is currently in the School of Biological Sciences. He received his Bachelor degree in Agriculture from Rajasthan Agricultural University, Master degree from Indian Agricultural Research Institute and PhD degree from the National Center for Biological Science. His research interests include social behaviors and manipulation of host behavior by parasites. Prof Vyas can be contacted by email at AVYAS@ntu.edu.sg

Mr Shaik Muhammad Amin is a Research Assistant from the Ageing Research Institute for Society and Education at NTU. Mr Amin can be contacted by email at Shaik.Amin@ntu.edu.sg

Mr Valentin Gulyás is a Research Assistant at the Department of Psychology, University of San Francisco. Mr Gulyás can be contacted by email at gulyas.valentin@gmail.com

Dr Parasuraman Padmanabhan is Head of Operations at the Cognitive Neuroimaging Centre, NTU. Dr Padmanabhan can be contacted by email at ppadmanabhan@ntu.edu.sg

|