|

by Cho Im Sik

ince the 1960s, when the state launched its public housing program, public housing has played an important role in the development of communities in Singapore, as it implies far more than the mere provision of housing space. The extensiveness of public housing throughout Singapore — where more than 80% of the resident population lives, develops social relationships, and shares common experiences — sets the foundation for the use of public housing for social cohesion as a conscious goal of the program in the city-state. ince the 1960s, when the state launched its public housing program, public housing has played an important role in the development of communities in Singapore, as it implies far more than the mere provision of housing space. The extensiveness of public housing throughout Singapore — where more than 80% of the resident population lives, develops social relationships, and shares common experiences — sets the foundation for the use of public housing for social cohesion as a conscious goal of the program in the city-state.

In this context, the design and provision of shared amenities and communal spaces within public housing neighborhoods plays a significant role in shaping communities. Therefore, it is important to rethink the role of public housing and its built environment in facilitating, encouraging, and deepening community bonding. This is more so given the fast changing social environment of a better informed and more vocal young population, a larger proportion of older residents, and increasing social diversity.

The Housing and Development Board (HDB), Singapore's housing authority, and the National University of Singapore (NUS) thus embarked on a research project in 2012 to study the impact of the HDB built environment on community bonding. This research is aligned with a key pillar of HDB's "Roadmap to Better Living in HDB Towns," which is to build community-centric towns. The study shed light on how existing facilities and amenities are used by the residents, how effective they have been in fostering social interactions among neighbors, and the current state of neighboring. Nine design strategies and six typologies were developed from these observations and a follow-up study was recently conducted during 2014-2015 to implement two recommended design typologies: Neighbourhood Incubator and Social Linkway.

Research Phase 1: Collaborative project with HDB, 2012-2014

This research studied the relationship between the built environment and community bonding in the context of Singapore's public housing estates. It particularly focused on understanding the relationship between usage of public amenities and community bonding in public housing neighborhoods. The aim of the study was to identify design principles that have facilitated community bonding, and uncover new design strategies to foster greater community interaction. Design principles that are crucial to facilitate community activities and enhance social interaction in common spaces have been distilled from the study for application in new housing precincts or those undergoing upgrading. This research studied the relationship between the built environment and community bonding in the context of Singapore's public housing estates. It particularly focused on understanding the relationship between usage of public amenities and community bonding in public housing neighborhoods. The aim of the study was to identify design principles that have facilitated community bonding, and uncover new design strategies to foster greater community interaction. Design principles that are crucial to facilitate community activities and enhance social interaction in common spaces have been distilled from the study for application in new housing precincts or those undergoing upgrading.

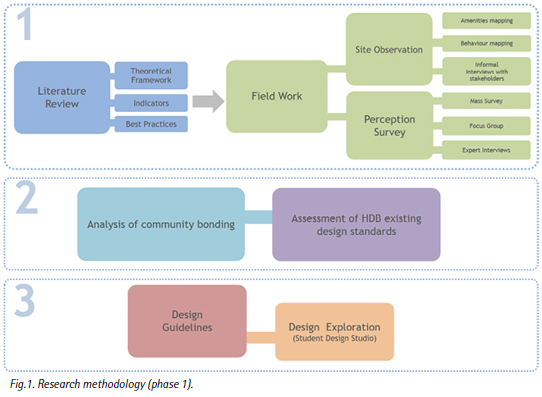

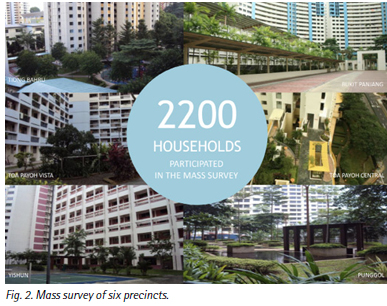

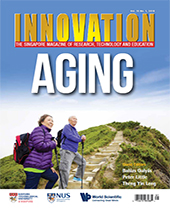

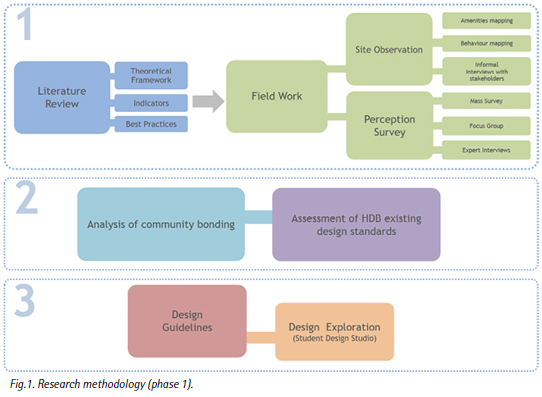

Through a review of the literature, mass survey, and focus group discussions, the research has uncovered a number of aspects that are pertinent to community bonding in  Singapore's public housing neighborhoods (Figure 1). A survey was conducted among 2,200 residents of different ages from six precincts: Tiong Bahru, Yishun, Toa Payoh Vista, Toa Payoh Central Horizon, Punggol, and Bukit Panjang. These sites represent the different HDB towns in different stage of their development which offers different types of amenities and facilities to facilitate community bonding. The respondents in the mass survey answered questions about their level of social interaction, sense of community and usage of neighborhood amenities, among many others (Figure 2). Six focus group discussions involving 80 residents were also conducted. All of these have contributed to a better understanding of the residents' usage patterns of public amenities at HDB estates, and help to identify designs that can facilitate better community interaction, as the survey results suggest that residents who frequently use a wide range of amenities in their precinct tend to report a stronger sense of place and belonging and responsibility for their precinct. In addition, the study also found that residents who live in the estate longer tend to have stronger neighborly relations. Lastly, the study also found that HDB precincts offer multiple opportunities for neighbors to meet — residents tend to encounter their neighbors casually in common areas; residents also meet at "third places" such as coffee shops and supermarkets; and playgrounds and fitness corners are popular with families with young children and the elderly. Singapore's public housing neighborhoods (Figure 1). A survey was conducted among 2,200 residents of different ages from six precincts: Tiong Bahru, Yishun, Toa Payoh Vista, Toa Payoh Central Horizon, Punggol, and Bukit Panjang. These sites represent the different HDB towns in different stage of their development which offers different types of amenities and facilities to facilitate community bonding. The respondents in the mass survey answered questions about their level of social interaction, sense of community and usage of neighborhood amenities, among many others (Figure 2). Six focus group discussions involving 80 residents were also conducted. All of these have contributed to a better understanding of the residents' usage patterns of public amenities at HDB estates, and help to identify designs that can facilitate better community interaction, as the survey results suggest that residents who frequently use a wide range of amenities in their precinct tend to report a stronger sense of place and belonging and responsibility for their precinct. In addition, the study also found that residents who live in the estate longer tend to have stronger neighborly relations. Lastly, the study also found that HDB precincts offer multiple opportunities for neighbors to meet — residents tend to encounter their neighbors casually in common areas; residents also meet at "third places" such as coffee shops and supermarkets; and playgrounds and fitness corners are popular with families with young children and the elderly.

However, a perceived sense of community and tolerance might not necessarily mean intense neighborly interaction, as the survey reported that the overall level of neighborhood interaction appears to be minimal and tends to decrease with greater physical distance. This suggests that "human-to-human bonding" is not as strong as "human-to-place bonding" (Figure 3). The study showed that the current state of neighbor-interaction in the HDB estates tends to be incidental and minimal. Most neighbors were found to frequently exchange greetings with each other, but they do not engage in behavior that requires a higher level of trust, such as lending/borrowing items from neighbors. Distance between the units also has an impact on neighborly interaction. The most intensive interaction was noted for immediate neighbors (e.g., same floor neighbors), with the interaction reducing sharply with distance.

Ultimately, the research shed light on how existing facilities and amenities in HDB precincts are used by residents, how effective they have been in fostering social interactions among neighbors, and the current state of neighborhood bonding in Singapore. Nine design strategies (Figure 4) and six typologies of community spaces (Figure 5) were developed from this investigation and a follow-up study (Phase 2) was conducted during 2014–2015 to implement the recommended design typologies in an existing public housing neighborhood. All of these typologies reflect the key principles of community bonding in terms of its physical characteristics (hardware), social programs and usage (software), and institutional setting (orgware).

Besides the impact of design on community interaction, the study also revealed that there are other components that are equally important. These include the social programming (software) and the institutional setting (orgware), as the sustainability of community-led projects highly depends on the level of organizational support that often drives and facilitates both physical and programmatic aspects of a neighborhood project. Well-planned events in public spaces can effectively bring people together, while relaxation of regulations gives residents more freedom to use public spaces, according to their needs and aspirations. Central to establishing a participatory approach to neighborhood planning and design are volunteerism and grassroots structures that involve a variety of stakeholders. These mechanisms are expected to lead to a deeper sense of ownership. Moving beyond the existing engagement practices in Singapore, which are broadly consultative in nature, the establishment of stronger and more well-structured institutional support systems can ensure sustainability and demonstrate social impact and capacity building.

Research Phase 2: Collaborative project with HDB, 2014-2015

The second phase of the research study (2014-2015) aimed to examine and implement possible mechanisms and platforms of participation, whereby the various stakeholders are included throughout the process of developing the proposed design typologies in an existing residential neighborhood, to encourage deeper social interaction and heighten the sense of community and belonging to a place. It aimed to create a participatory system that can function under Singapore's unique circumstances, and provide the community with space to incubate new initiatives, assume new responsibilities, and take part in the decision-making process through a scheme called Hello Neighbour! This project has examined approaches in which new spatial practices for community-centric neighborhood planning can take place in Singapore's heartland.

A participatory design approach, developed as one of the key strategies for community bonding in Phase 1 of the study, was adopted to "co-create" public spaces in housing estates with the residents, beginning with their involvement at the planning stage and culminating in the construction of two new community spaces: the Neighbourhood Incubator and the Social Linkway. These design typologies were chosen as they were deemed suitable for testing in existing neighborhoods for a start and do not require lengthy, complex, or major construction work, thereby allowing HDB to assess its effectiveness within the next one to two years. They also put a good range of the various design strategies recommended to the test.

The study in Phase 1 revealed the importance of providing a one-stop community hub that can house community activities and incubate ground-up initiatives. Such a Neighbourhood Incubator typology requires strong community leadership to succeed. One possibility is to co-locate such spaces with the Residents' Committee (RC) centers. Therefore, Neighbourhood Incubator converts void deck spaces next to the RC centers to flexible community living areas and facilitate community efforts such as events and workshops. The residents jointly determine how the space is used depending on their needs and wishes. On the other hand, the previous research (Phase 1) has shown that linkways in Singapore's neighborhoods are one of the most frequently used amenities where residents meet their neighbors incidentally. Social Linkway introduces communal functions and facilities such as nodes of interest, seats, sculptures or exhibits to the linkways to encourage residents to linger, thereby transforming transitory linkways into more meaningful social spaces; in turn, this change leads to increased chances for incidental neighboring.

Other than validating the effectiveness of these two design typologies in promoting bonding, this follow-up study put to test a three-pronged approach to community building, encompassing attention not just to the hardware (design), but also the software (programs) and orgware (policies and organizational support). Moreover, as advocated in Phase 1 of the study and by numerous other studies, active participation of the community and various stakeholders in the planning and design of their neighborhoods would encourage a sense of ownership and create stronger bonds among different members of the community. Hence, in the project warmly coined as Hello Neighbour!, the study adopted a new community participatory design approach to co-creating with the residents of Tampines (a public housing neighborhood in Singapore) a unique Neighbourhood Incubator and a Social Linkway with interventions at various points along a walk way that runs through Tampines Central. Tampines Central was selected as the prototype site owing to its existing infrastructure (long linkway between Tampines Central Park and nearby neighborhood center), as well as the involvement of several key partners in the community. The size of the site (30 blocks) was also regarded as appropriate for meaningful engagement.

Research Methodology (Phase 2)

There is no simple solution or standard approach to identify an effective engagement method for all neighborhoods. However, effective tools for participation must be designed to heighten the human and social processes that underline the exchange of knowledge, skills, and resources. Through an intensive community engagement process, the research was conducted in the form of Participatory Action Research (PAR) whereby the researchers were actively engaged in the community design participation process. The PAR approach was adopted because it could provide dynamic solutions to the following issues: (1) complex processes of participatory neighborhood planning, which involve various stakeholders who often have different backgrounds and views; and (2) the dynamic process of community engagement that requires a flexible and adaptable approach, which can be continuously modified and improved.

With this approach, a platform for collaboration among different stakeholders involved in or affected by the research study was created in which the community members were considered co-researchers, to address questions and issues pertaining to this project. In addition to the HDB and the local community in Tampines, the research team collaborated closely with local stakeholders, including the Tampines town council (TC) and the chairpersons of the three RCs within the project site (Tampines Ville, Tampines Parkview, and Tampines Palmwalk). The People's Association (PA)'s Tampines Central constituency office was also involved in the project as a member of the working committee. This method allowed a series of collective inquiries and experimentation followed by continuous reflection and evaluation to refine the approach.

Data collection was done throughout the participation process, whereby the data gathered from each action/step was reflected back to the whole research process for the improvement of the designed mechanism. This took place over two phases: (1) review of existing community design participatory methods through literature studies, and (2) review of both the proposed design guidelines and design typologies through community participatory methodologies such as interviews with experts, interactive exhibitions, community outreach events/pop-up booths with exit questionnaires, a focus group discussion with residents and participating experts (working committee), a design workshop, informal interviews, design construction, volunteer programs, and co-creation events on site.

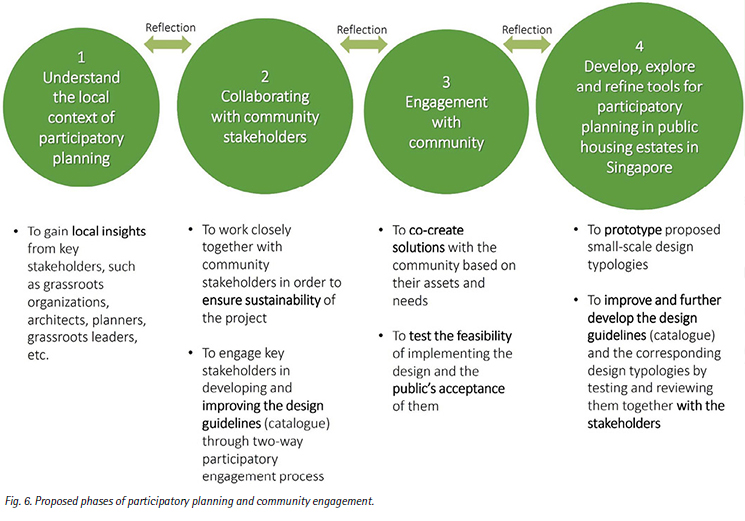

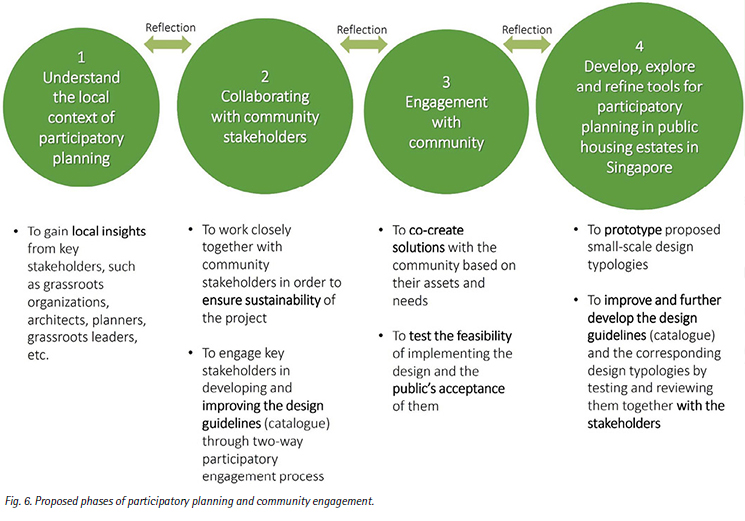

After reviewing several models of neighborhood planning, this study has identified the importance of various clearly defined yet flexible steps of planning with the community and proposed the initial model of participatory planning and community engagement, consisting of four main phases as indicated below.

A. Fieldwork

The project has reached out to the residents living in a public housing neighborhood in Tampines Central that consists of 5,000 household units, specifically those in block numbers 830 to 863 at Tampines Street 82/83 and Avenue 5 in Singapore. Several site visits were conducted to observe and experience the daily life of the residents, map their meeting places, build relationships with the local connectors, and locate possible sites for intervention.Existing assets of the neighborhood such as community connector locations, available spaces, nearby institutions, and community gathering places were also mapped during the process.

B. Community Outreach Events/Pop-up Booths with Exit Questionnaires

These events aimed at reaching out to a larger community who might not participate in the focus group discussion and the design workshop. Three pop-up events were held to display the project and its progress, and seek residents’ feedback. These events/pop-up booths were held in public spaces such as void decks, green open spaces, and hard courts within the neighborhood (Figure 7). The pop-up events happened at different times of the day on both weekdays and weekends to tap into different pedestrian flows as well as residents of different demographic groups to reach as many people as possible. These events aimed at reaching out to a larger community who might not participate in the focus group discussion and the design workshop. Three pop-up events were held to display the project and its progress, and seek residents’ feedback. These events/pop-up booths were held in public spaces such as void decks, green open spaces, and hard courts within the neighborhood (Figure 7). The pop-up events happened at different times of the day on both weekdays and weekends to tap into different pedestrian flows as well as residents of different demographic groups to reach as many people as possible.

C. Focus Group Discussion (FGD)

One FGD with residents was conducted to further understand the neighborhood and the residents regarding their daily activities, gathering spots, nodes, landmarks, and their thoughts on the quality of the current neighborhood amenities. The FGD also gathered residents' ideas for creating a prototype of the proposed design typologies (i.e., the Neighbourhood Incubator and the Social Linkway).

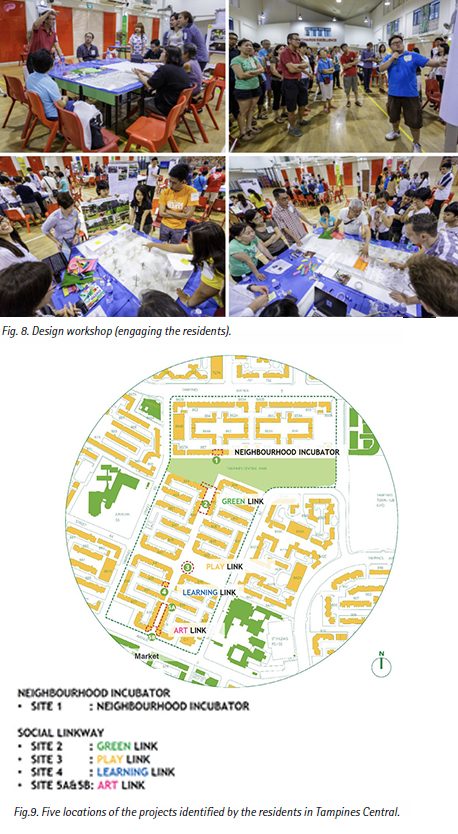

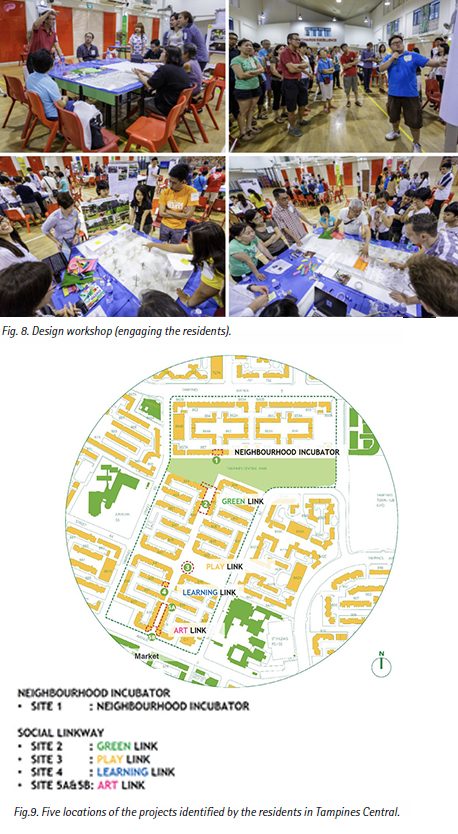

D. Design Workshop

One design workshop was conducted to engage the residents in visualizing their ideas and aspirations for constructing the proposed design typologies (Figure 8). The participants identified five locations within Tampines that could be spruced up to be active community spaces (Figure 9). The Neighbourhood Incubator (Figure 10) at Tampines block 857 could be converted easily into a Wi-Fi-enabled workshop space to facilitate the conduct of workshops by the community, e.g., health talks, art lessons, etc. The space, to be equipped with moveable stools, could also be used by the residents for get-togethers, such as potluck sessions or flea markets. The four remaining locations would make up the Social Linkway that will comprise four segments: Green Link, Play Link, Learning Link and Art Link. While each segment has its unique characteristics, they also cluster residents involved in different activities together for greater interaction opportunities. The Green Link forms the entrance of the link way and features spaces for community gardening. The void deck at block 839 will be converted into the Learning Link (Figure 11), with a cozy reading and kopi corner. Under the Play Link, the area next to the existing playground and basketball court will be given a fresh lease on life with a new circular hardcourt and additional seats. Finally, the Art Link showcases murals and/or art pieces co-created by the community. One design workshop was conducted to engage the residents in visualizing their ideas and aspirations for constructing the proposed design typologies (Figure 8). The participants identified five locations within Tampines that could be spruced up to be active community spaces (Figure 9). The Neighbourhood Incubator (Figure 10) at Tampines block 857 could be converted easily into a Wi-Fi-enabled workshop space to facilitate the conduct of workshops by the community, e.g., health talks, art lessons, etc. The space, to be equipped with moveable stools, could also be used by the residents for get-togethers, such as potluck sessions or flea markets. The four remaining locations would make up the Social Linkway that will comprise four segments: Green Link, Play Link, Learning Link and Art Link. While each segment has its unique characteristics, they also cluster residents involved in different activities together for greater interaction opportunities. The Green Link forms the entrance of the link way and features spaces for community gardening. The void deck at block 839 will be converted into the Learning Link (Figure 11), with a cozy reading and kopi corner. Under the Play Link, the area next to the existing playground and basketball court will be given a fresh lease on life with a new circular hardcourt and additional seats. Finally, the Art Link showcases murals and/or art pieces co-created by the community.

The outcomes of this project were two-fold. One relates to the effectiveness of the typologies in encouraging deeper social interaction among neighbors. The other relates to the success of the co-creation and engagement process, i.e., whether the engagement methodology and channels used have an impact on enhancing the residents’ sense of identity and ownership. More than 1,000 residents and relevant stakeholders have been engaged during the process. The project has generated positive outcomes such as more bottom-up initiatives organized by the residents, increased use of newly created communal spaces, and deeper neighborly interactions.

The research has shown that an established framework and mechanism for participation is needed to create a platform for collaborative planning where community leaders, professionals, and residents can work together, brainstorm, and envision plans for the neighborhood. The research findings also point to the fact that the presence of a neutral facilitator and supporting organizations are crucial for implementing effective and meaningful participatory processes. They can act as catalysts for development and become facilitators that assist and stimulate community-based initiatives. They should be neutral so as to be the mediators between the government agency/authority and the beneficiary community. The presence of community leaders is important as well. For these leaders to be effective, training in technical and social skills such as conflict resolutions, organizing communities, conducting meetings and so on, is necessary. It could be a mechanism that allows access to knowledge, skills, and resource sharing. A residents’ volunteer program called the "Friends of Tampines" was proposed for those keen to volunteer in specific roles, such as community designers and space activators, to help realize the plans. It was also introduced to identify and nurture residents (who are not among the existing grassroots leaders) driven by their interest and passion for certain activities to empower them to co-create and sustain initiatives for the community over the long run.

Singapore's recent move towards a more inclusive and participatory style of leadership has facilitated more awareness about the importance of community participation in the local context. This research project has been initiated in line with such a changing approach to neighborhood planning, and has attempted to develop a participatory mechanism that can work in Singapore's context to encourage deeper social cohesion and community bonding through the involvement of the community and stakeholders in the planning process. However, achieving inclusivity and sustainability remains a challenge, especially in a multicultural society such as that of Singapore. More emphasis should be placed on engaging everyone in a locality, including hard-to-reach groups or those with traditionally low involvement profiles. Even though various engagement tools and methods have been experimented with during the process, there is still room to explore more transparent and open platforms for participation and communication. This will enhance the engagement of the community in creating community visions together, examining and implementing possible mechanisms of participation whereby various stakeholders are included. It will also empower members of the community to contribute in their own ways to the processes of decision-making and community building. Singapore's recent move towards a more inclusive and participatory style of leadership has facilitated more awareness about the importance of community participation in the local context. This research project has been initiated in line with such a changing approach to neighborhood planning, and has attempted to develop a participatory mechanism that can work in Singapore's context to encourage deeper social cohesion and community bonding through the involvement of the community and stakeholders in the planning process. However, achieving inclusivity and sustainability remains a challenge, especially in a multicultural society such as that of Singapore. More emphasis should be placed on engaging everyone in a locality, including hard-to-reach groups or those with traditionally low involvement profiles. Even though various engagement tools and methods have been experimented with during the process, there is still room to explore more transparent and open platforms for participation and communication. This will enhance the engagement of the community in creating community visions together, examining and implementing possible mechanisms of participation whereby various stakeholders are included. It will also empower members of the community to contribute in their own ways to the processes of decision-making and community building.

All these attempts and explorations will offer support for more participatory and inclusive approach to community-based urban development, which reflects the aspirations of contemporary and future Singapore, with increasing advocacy for greater involvement of communities in the planning process of their living environments. All these attempts and explorations will offer support for more participatory and inclusive approach to community-based urban development, which reflects the aspirations of contemporary and future Singapore, with increasing advocacy for greater involvement of communities in the planning process of their living environments.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on two research projects: "A Study on the Impact of the Built Environment on Community Bonding (2012-2014)" and "A Study on the Application of Design Recommendations to Foster Community Bonding – Hello Neighbour (2014-2015)." Both are collaborations between the National University of Singapore (NUS) and Singapore's Housing and Development Board (HDB). As Principal Investigator for both projects, the author would like to thank HDB for their support and funding, Associate Professor Ho Kong Chong (Department of Sociology, NUS) who was involved in the two research projects as sociology consultant, and the research team members at the Centre for Sustainable Asian Cities (CSAC) at the School of Design and Environment, NUS, for their contributions to these research projects.

Cho Im Sik is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, at the National University of Singapore where she serves as the leader for urban studies research and teaching and as principal investigator for many research projects funded by the key government agencies in Singapore. Her principal research interests are in urban space planning for sustainable high-density environments, and design for social sustainability involving community-based, participatory approaches. Her research interests address the challenges and opportunities that Asian cities face with accelerating social change, especially in the context of neighborhood planning, focusing on the social dimension of sustainable development. She has served as a reviewer for the National Research Foundation of Singapore (2014-2017) and South Korea (2015). Her recent publications as lead author include Towards an Integrated Urban Space Framework for Emerging Urban Conditions in a High-density Context in the Journal of Urban Design (2015); Re-framing Urban Space: Urban Design for Emerging Hybrid and High-Density Conditions (Routledge, 2016); and Community-based Urban Development: Evolving Urban Paradigms in Singapore and Seoul (Springer, forthcoming).

For more information about this article, please contact Assistant Professor Cho Im Sik at akicis@nus.edu.sg

Click here to download the full issue for USD 6.50 Click here to download the full issue for USD 6.50

|

ince the 1960s, when the state launched its public housing program, public housing has played an important role in the development of communities in Singapore, as it implies far more than the mere provision of housing space. The extensiveness of public housing throughout Singapore — where more than 80% of the resident population lives, develops social relationships, and shares common experiences — sets the foundation for the use of public housing for social cohesion as a conscious goal of the program in the city-state.

ince the 1960s, when the state launched its public housing program, public housing has played an important role in the development of communities in Singapore, as it implies far more than the mere provision of housing space. The extensiveness of public housing throughout Singapore — where more than 80% of the resident population lives, develops social relationships, and shares common experiences — sets the foundation for the use of public housing for social cohesion as a conscious goal of the program in the city-state.

This research studied the relationship between the built environment and community bonding in the context of Singapore's public housing estates. It particularly focused on understanding the relationship between usage of public amenities and community bonding in public housing neighborhoods. The aim of the study was to identify design principles that have facilitated community bonding, and uncover new design strategies to foster greater community interaction. Design principles that are crucial to facilitate community activities and enhance social interaction in common spaces have been distilled from the study for application in new housing precincts or those undergoing upgrading.

This research studied the relationship between the built environment and community bonding in the context of Singapore's public housing estates. It particularly focused on understanding the relationship between usage of public amenities and community bonding in public housing neighborhoods. The aim of the study was to identify design principles that have facilitated community bonding, and uncover new design strategies to foster greater community interaction. Design principles that are crucial to facilitate community activities and enhance social interaction in common spaces have been distilled from the study for application in new housing precincts or those undergoing upgrading.

Singapore's public housing neighborhoods (Figure 1). A survey was conducted among 2,200 residents of different ages from six precincts: Tiong Bahru, Yishun, Toa Payoh Vista, Toa Payoh Central Horizon, Punggol, and Bukit Panjang. These sites represent the different HDB towns in different stage of their development which offers different types of amenities and facilities to facilitate community bonding. The respondents in the mass survey answered questions about their level of social interaction, sense of community and usage of neighborhood amenities, among many others (Figure 2). Six focus group discussions involving 80 residents were also conducted. All of these have contributed to a better understanding of the residents' usage patterns of public amenities at HDB estates, and help to identify designs that can facilitate better community interaction, as the survey results suggest that residents who frequently use a wide range of amenities in their precinct tend to report a stronger sense of place and belonging and responsibility for their precinct. In addition, the study also found that residents who live in the estate longer tend to have stronger neighborly relations. Lastly, the study also found that HDB precincts offer multiple opportunities for neighbors to meet — residents tend to encounter their neighbors casually in common areas; residents also meet at "third places" such as coffee shops and supermarkets; and playgrounds and fitness corners are popular with families with young children and the elderly.

Singapore's public housing neighborhoods (Figure 1). A survey was conducted among 2,200 residents of different ages from six precincts: Tiong Bahru, Yishun, Toa Payoh Vista, Toa Payoh Central Horizon, Punggol, and Bukit Panjang. These sites represent the different HDB towns in different stage of their development which offers different types of amenities and facilities to facilitate community bonding. The respondents in the mass survey answered questions about their level of social interaction, sense of community and usage of neighborhood amenities, among many others (Figure 2). Six focus group discussions involving 80 residents were also conducted. All of these have contributed to a better understanding of the residents' usage patterns of public amenities at HDB estates, and help to identify designs that can facilitate better community interaction, as the survey results suggest that residents who frequently use a wide range of amenities in their precinct tend to report a stronger sense of place and belonging and responsibility for their precinct. In addition, the study also found that residents who live in the estate longer tend to have stronger neighborly relations. Lastly, the study also found that HDB precincts offer multiple opportunities for neighbors to meet — residents tend to encounter their neighbors casually in common areas; residents also meet at "third places" such as coffee shops and supermarkets; and playgrounds and fitness corners are popular with families with young children and the elderly.

These events aimed at reaching out to a larger community who might not participate in the focus group discussion and the design workshop. Three pop-up events were held to display the project and its progress, and seek residents’ feedback. These events/pop-up booths were held in public spaces such as void decks, green open spaces, and hard courts within the neighborhood (Figure 7). The pop-up events happened at different times of the day on both weekdays and weekends to tap into different pedestrian flows as well as residents of different demographic groups to reach as many people as possible.

These events aimed at reaching out to a larger community who might not participate in the focus group discussion and the design workshop. Three pop-up events were held to display the project and its progress, and seek residents’ feedback. These events/pop-up booths were held in public spaces such as void decks, green open spaces, and hard courts within the neighborhood (Figure 7). The pop-up events happened at different times of the day on both weekdays and weekends to tap into different pedestrian flows as well as residents of different demographic groups to reach as many people as possible.

One design workshop was conducted to engage the residents in visualizing their ideas and aspirations for constructing the proposed design typologies (Figure 8). The participants identified five locations within Tampines that could be spruced up to be active community spaces (Figure 9). The Neighbourhood Incubator (Figure 10) at Tampines block 857 could be converted easily into a Wi-Fi-enabled workshop space to facilitate the conduct of workshops by the community, e.g., health talks, art lessons, etc. The space, to be equipped with moveable stools, could also be used by the residents for get-togethers, such as potluck sessions or flea markets. The four remaining locations would make up the Social Linkway that will comprise four segments: Green Link, Play Link, Learning Link and Art Link. While each segment has its unique characteristics, they also cluster residents involved in different activities together for greater interaction opportunities. The Green Link forms the entrance of the link way and features spaces for community gardening. The void deck at block 839 will be converted into the Learning Link (Figure 11), with a cozy reading and kopi corner. Under the Play Link, the area next to the existing playground and basketball court will be given a fresh lease on life with a new circular hardcourt and additional seats. Finally, the Art Link showcases murals and/or art pieces co-created by the community.

One design workshop was conducted to engage the residents in visualizing their ideas and aspirations for constructing the proposed design typologies (Figure 8). The participants identified five locations within Tampines that could be spruced up to be active community spaces (Figure 9). The Neighbourhood Incubator (Figure 10) at Tampines block 857 could be converted easily into a Wi-Fi-enabled workshop space to facilitate the conduct of workshops by the community, e.g., health talks, art lessons, etc. The space, to be equipped with moveable stools, could also be used by the residents for get-togethers, such as potluck sessions or flea markets. The four remaining locations would make up the Social Linkway that will comprise four segments: Green Link, Play Link, Learning Link and Art Link. While each segment has its unique characteristics, they also cluster residents involved in different activities together for greater interaction opportunities. The Green Link forms the entrance of the link way and features spaces for community gardening. The void deck at block 839 will be converted into the Learning Link (Figure 11), with a cozy reading and kopi corner. Under the Play Link, the area next to the existing playground and basketball court will be given a fresh lease on life with a new circular hardcourt and additional seats. Finally, the Art Link showcases murals and/or art pieces co-created by the community.

Singapore's recent move towards a more inclusive and participatory style of leadership has facilitated more awareness about the importance of community participation in the local context. This research project has been initiated in line with such a changing approach to neighborhood planning, and has attempted to develop a participatory mechanism that can work in Singapore's context to encourage deeper social cohesion and community bonding through the involvement of the community and stakeholders in the planning process. However, achieving inclusivity and sustainability remains a challenge, especially in a multicultural society such as that of Singapore. More emphasis should be placed on engaging everyone in a locality, including hard-to-reach groups or those with traditionally low involvement profiles. Even though various engagement tools and methods have been experimented with during the process, there is still room to explore more transparent and open platforms for participation and communication. This will enhance the engagement of the community in creating community visions together, examining and implementing possible mechanisms of participation whereby various stakeholders are included. It will also empower members of the community to contribute in their own ways to the processes of decision-making and community building.

Singapore's recent move towards a more inclusive and participatory style of leadership has facilitated more awareness about the importance of community participation in the local context. This research project has been initiated in line with such a changing approach to neighborhood planning, and has attempted to develop a participatory mechanism that can work in Singapore's context to encourage deeper social cohesion and community bonding through the involvement of the community and stakeholders in the planning process. However, achieving inclusivity and sustainability remains a challenge, especially in a multicultural society such as that of Singapore. More emphasis should be placed on engaging everyone in a locality, including hard-to-reach groups or those with traditionally low involvement profiles. Even though various engagement tools and methods have been experimented with during the process, there is still room to explore more transparent and open platforms for participation and communication. This will enhance the engagement of the community in creating community visions together, examining and implementing possible mechanisms of participation whereby various stakeholders are included. It will also empower members of the community to contribute in their own ways to the processes of decision-making and community building.

All these attempts and explorations will offer support for more participatory and inclusive approach to community-based urban development, which reflects the aspirations of contemporary and future Singapore, with increasing advocacy for greater involvement of communities in the planning process of their living environments.

All these attempts and explorations will offer support for more participatory and inclusive approach to community-based urban development, which reflects the aspirations of contemporary and future Singapore, with increasing advocacy for greater involvement of communities in the planning process of their living environments.

Click here to download the full issue for USD 6.50

Click here to download the full issue for USD 6.50